Hope Floats

September 4, 2020

In times of uncertainty

September 17, 2020Louise Robson, Creative Director at Wigan STEAM, and Curious Minds CASE fellow, writes a provocation on the importance and necessity of including arts and culture as an integral part of the recovery curriculum.

On the first day of the first CASE (Culture and Arts Schools Experts) residential last November, we spent some time studying a number of current government policies and studies relating to education. We read these documents with the knowledge that there was an upcoming general election which could have rendered many of these documents irrelevant to some extent. That in itself was enough to demonstrate the uncertainty that schools and education professionals face.

Fast forward six months and life has taken an unexpected turn which makes the uncertainty we felt at that point seem minute in comparison. We find ourselves in the midst of a global pandemic. For months, schools were closed to all but key worker's children, with no real idea of when they would go back to normal. Parents were shocked into home-schooling and now, as schools attempt to navigate a return for the new academic year, the panic of children ‘catching-up’ has taken hold amongst many parents, teachers, and government figures.

It’s true that there is work to do, but catching-up on missed lessons is just one piece of the puzzle. Barry Carpenter, a Professor of Mental Health in Education, recently developed a ‘Recovery Curriculum’ which acknowledges the other losses students have faced during this period and sets out a framework to allow for recovery and healing of the trauma, anxiety, and bereavement that many children and young people will be experiencing as a result of the pandemic.

Fast forward six months and life has taken an unexpected turn which makes the uncertainty we felt at that point seem minute in comparison. We find ourselves in the midst of a global pandemic. For months, schools were closed to all but key worker's children, with no real idea of when they would go back to normal. Parents were shocked into home-schooling and now, as schools attempt to navigate a return for the new academic year, the panic of children ‘catching-up’ has taken hold amongst many parents, teachers, and government figures.

It’s true that there is work to do, but catching-up on missed lessons is just one piece of the puzzle. Barry Carpenter, a Professor of Mental Health in Education, recently developed a ‘Recovery Curriculum’ which acknowledges the other losses students have faced during this period and sets out a framework to allow for recovery and healing of the trauma, anxiety, and bereavement that many children and young people will be experiencing as a result of the pandemic.

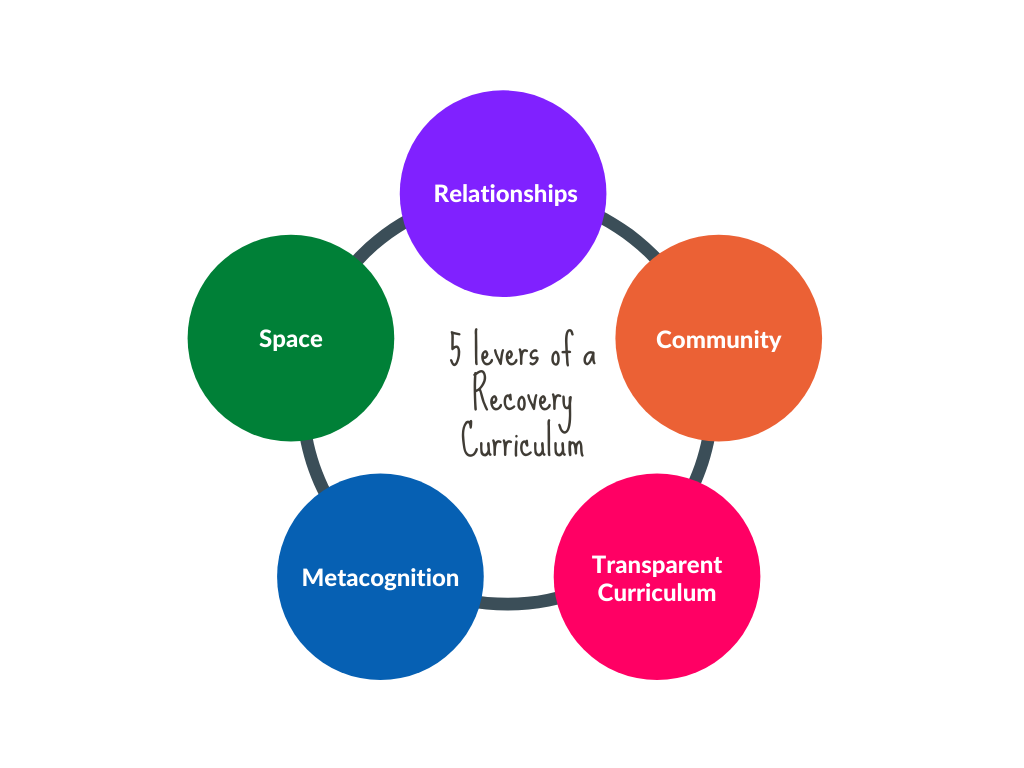

The framework is built on five levers (relationships, community, transparent curriculum, metacognition, and space) which he recommends are to be used by schools to produce a curriculum that allows for recovery whilst “reigniting the flame of learning in each child”. Within this recovery curriculum there is room for missed learning to be ‘caught-up’ on, but it recommends that this be student-led, and it’s by no means the priority. Instead, ‘catch-up’ is placed on a level playing field alongside students rebuilding relationships, regaining confidence and trust, healing their identity and sense of belonging, and reflecting on their existing experience and skills.

‘Catch-up’ is placed on a level playing field alongside students rebuilding relationships, regaining confidence and trust, healing their identity and sense of belonging, and reflecting on their existing experience and skills.

The term ‘catch-up’ is also damaging when we consider that the reason why children have missed lessons is because they’ve been living through a global pandemic. How much patience, resilience, resourcefulness and creativity might children have developed during this time?

Guy Claxton and Bill Lucas in their book ‘Educating Ruby’, describe a ‘domestic curriculum’, acknowledging that learning is not exclusive to school:

Guy Claxton and Bill Lucas in their book ‘Educating Ruby’, describe a ‘domestic curriculum’, acknowledging that learning is not exclusive to school:

Preparing young people to thrive in a tricky world is not just the job of schools and teachers. Parents are educators too. The way we talk to our kids, the kinds of rituals we create for them around mealtimes and bedtimes, the activities we encourage, the role models we provide, the materials we place within their reach, the kinds of ‘fun’ we lay on for them; all of these carry messages that influence their growing minds.

In being at home children have not just switched off their brains and become resistant to taking in knowledge and developing new skills. Of course, there will be children out there who are gaining less than others in their domestic environment and careful attention needs to be paid to these children, but this only strengthens the argument for a gentle, recovery-based approach which puts wellbeing before catching up on knowledge.

There are so many reasons why arts and culture should play a central role within this recovery curriculum: it has the ability to improve mental health and wellbeing, it helps us to communicate at our most vulnerable, it brings people together, and can help people to develop a sense of belonging.

There are so many reasons why arts and culture should play a central role within this recovery curriculum: it has the ability to improve mental health and wellbeing, it helps us to communicate at our most vulnerable, it brings people together, and can help people to develop a sense of belonging. However, there’s no doubt that this pandemic has harmed and will continue to harm the arts and cultural landscape, and it’s a huge worry that the need for schools to ‘catch-up’ will result in arts and culture being dropped altogether in favour of academic subjects - something which has always been a very real threat without the presence of a pandemic. We’re also facing the prospect that, understandably, schools won’t be allowing visitors or going on trips to cultural venues for a significant period of time.

On the final episode of Grayson’s Art Club, when asked what the show has shown him about the people of Great Britain, comedian and amateur artist Joe Lycett said:

“We’re a laugh aren’t we?... We’re all just making things to get us through. And the art world, as I’m sure you’re aware, has felt serious and heavy and unapproachable and not for the likes of us. And this programme has gone a big way to making it feel like it is for everyone.”

There’s a reason why Grayson Perry had the nation sending him artwork each week; why almost every household displayed artwork in the window; why artists and illustrators from across the globe held online draw-a-longs and art challenges that saw thousands participate; why going for a walk through the woods meant you happened upon colourful painted rocks and sculptures containing messages of hope; why music venues and theatres started live streaming performances; why arts organisations continued to meet with groups via zoom: it helped to get us through, and in September, children will still be trying to get through - the pandemic has united us all in that.

It helped to get us through, and in September, children will still be trying to get through - the pandemic has united us all in that.

The current landscape has forced cultural organisations and creative freelancers to develop new ways of working when our only method of delivery is from a distance - some are experimenting with delivering content online, developing resource packs and delivering them to doorsteps, creating virtual exhibition tours and online exhibitions, and holding events via Zoom. All of these things come with their own issues and we’re not always getting it right - but there is an opportunity here for us to consider new ways of working with schools that weren’t considered pre-pandemic, that have the potential to provide new (and potentially more accessible) routes for children and young people to engage with arts and culture.

Education settings are going to be more difficult than ever to penetrate due to the pressures on teachers to get students ‘caught-up’, but there’s even more reason to fight to keep arts and culture on the table - we don’t have any choice but to find new ways of keeping it there.

Could we facilitate virtual workshops with artists, livestream theatre productions to assembly halls, run virtual CPD for teachers, lend or donate resources and equipment, or open up our online platforms for students to produce virtual exhibitions? Going online has its pitfalls but there is potential there, and for the next year or two using digital technology to provide pathways between arts and cultural organisations and schools is more than likely going to be the route that needs to be taken. Education settings are going to be more difficult than ever to penetrate due to the pressures on teachers to get students ‘caught-up’, but there’s even more reason to fight to keep arts and culture on the table - we don’t have any choice but to find new ways of keeping it there.

In his book ‘Creative Schools’, Sir Ken Robinson said, “Education is about living people, not inanimate things. If we think of students as products or data points, we misunderstand how education should be”. ‘Catching-up’ on the curriculum is just one piece of the very complicated puzzle, and as schools return, a recovery curriculum which has room for arts and culture must be considered and implemented to allow for gentle recovery amongst children and young people. This is not a time for the arts to be side-lined - it’s an opportunity to demand that room be made, for arts and culture to truly belong to everyone, and for the arts to be valued as an important tool for healing a generation of children who are living through a period of profound social disorder.